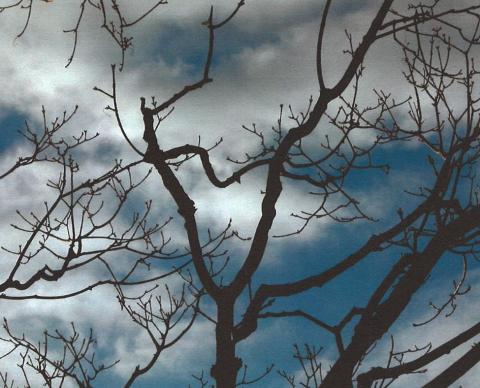

By the river it is cool and gray at last after a night of longed-for rain, however intermittent. Mist this morning clung to the trees, but it is gone now, leaving the caress of quiet moist air. The river is low, the banks brown, rock outcroppings breaking the water; but yet it flows, an ancient witness; as is the moss, growing up the north side of the oaks and box elders and sycamores, whose branches, sparse with brown and yellow leaves, form a wild weave against the pewter sky. A heron, guardian of edges, rises from the mud and glides in a wide arc to other shore.

I am here because the rocks and arrows hurled at all I have known, and all that I love, reached a new level of ferocity last week, and it seems that the speed and strength of the barrage will be relentless. Even after years of preparatory soul work, suddenly I can barely breathe. I thought the humbling might continue to creep toward us, with some mercy. Instead, the gods of mayhem spurred the horses.

In the wake of this, words have swirled: words to soothe, advise, comfort, inspire. I have passed them on, shared them; I am grateful for them all. But what I need may not be the call to march forward, to align with the highest benchmarks of humanity, to hold fast and to take skillful action, to neither wince nor flail. I need refugia and the wisdom of ancient beings like a river, trees, and moss.

Kathleen Dean Moore speaks of refugia in her book Great Tide Rising. Refugia are pockets of safety, tiny coverts where life hides from destruction, secret shelters out of which new life emerges. Refugia are why Mount Saint Helen’s mountainsides are lushly covered with grasses, prairie lupines, and alders, despite the eruption that erased 1,300 feet of the mountain and burned 230 square miles of forest.

Refugia are small and hidden and full of darkness, but they are potent. They may be characterized as sanctuaries, but they are cauldrons, wombs, incubators. They are everywhere: in a poem, the eyes of a friend, a preserved landscape, a permaculture garden, a prayer in the wild.

So I have come to the river, the stone cliffs, the moss growing on those old trees. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “Mosses, I think, are like time made visible…The mosses remember that this is not the first time the glaciers have melted…”, or a political system has failed. Kimmerer points out that mosses document a passage of time that is not linear. “…the knowledge we need,” she says, “is already within the circle; we just have to remember to find it again…”

There are beings on this planet older by far than elections and democracy, older than civilization, older even than the human imagination. They are here to turn to, to help us begin to breathe again. Four hundred fifty million years ago mosses traveled from the primordial waters and began a great experiment in evolution, as Kimmerer writes, “an experiment of which we are all a part, whose ending is unwritten.”

Unwritten, and unknown. Some would say that is the definition of hope, an invitation to act out of our places of refugia, out of the wisdom of mosses, rather than reaction to the certainty of the dystopia we think we know has arrived.

Bayo Akomolafe says, “the way is awkward, not forward”. Perhaps that is the challenge: To stumble around, feeling for the opening of the path that is hardly a path at all, is many-branching, possibly strange, and made by walking. To listen to wisdom and voices beyond the scope of human intelligence, to other ways of knowing rising from other places of power, to tune to the rhythm of the river and the whispers of moss.